This Sunday three teams will drop out of the English Premier League. What will it cost them? Can they return?

This Sunday sees the final round of matches in the English Premier League – “the best league in the world”, watched by billions of people around the planet. A season which began back in August finally reaches its end. I can’t say climax, as virtually all the major issues have already been decided: Manchester City are champions and Manchester United – with a gloomy Jose Mourinho refusing to celebrate – will finish as runners-up.

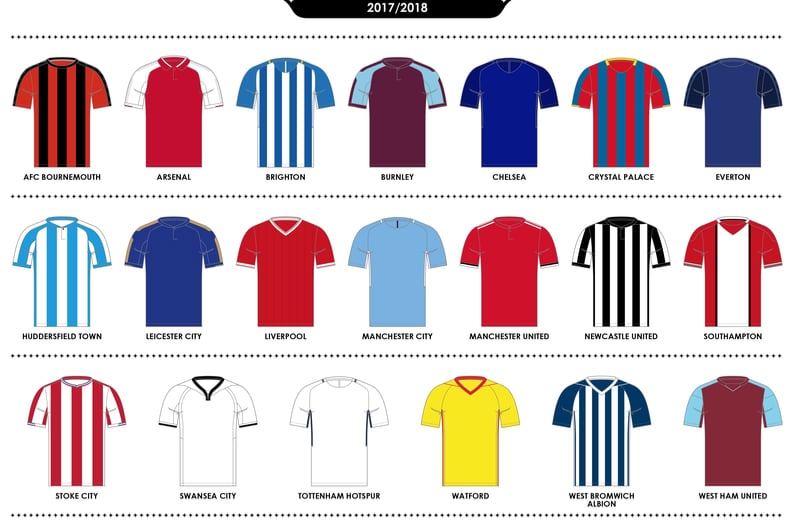

But what about the other end of the table? West Bromwich Albion and Stoke City have already been relegated and – barring a miracle – they will be joined by Swansea City. What does the future hold for these three teams? And specifically, what are the financial implications of dropping out of the Premier League?

Relegation: an expensive business

We wrote recently about the “richest prize in sport” – the Championship play-off final which will take place on May 26 and see the winners promoted to the Premier League and earning the £150m ($203m) in TV revenue, gate receipts and sponsorship that goes with it.

…So going in the opposite direction is a very expensive business. Just how expensive will it be for West Brom, Stoke, and Swansea – and what are their prospects of returning to the promised land? With figures for this season not yet certain, I am going to use the example of Sunderland, relegated last year along with Hull City and Middlesbrough.

Hard times on Wearside

There’s no getting away from it, the difference in revenue between the Premier League and the Championship is enormous.

Including foreign broadcasting rights, the Premier League TV deal tops £8bn ($10.8bn). From this, each club receives at least £100m ($135m), with the payment increasing the higher up the League a club finishes. Contrast this with the Championship where the average TV revenue is between £5m and £6m ($6.7–8.1m).

Sponsorship and commercial activities will also take a huge hit. Of the teams in the Championship, Leeds United earned the most from commercial activities during the 2015–16 season. The figure was around £15m ($20.3m) – roughly £10m ($13.5m) less than Sunderland earned, despite struggling in the Premier League. So, relegated teams will take a big hit from commercial revenues – and also from matchday attendances, with the average attendance in the Championship around 15,000 less than in the Premier League. With the greatest possible respect, Accrington Stanley will take rather fewer supporters to Sunderland than Manchester United did.

Parachute payments

Relegation from the Premier League is cushioned by “parachute payments,” with the clubs receiving a proportion of the income they would have received had they stayed in the Premier League. In the case of Sunderland, this would have been around £55m in season 2017–18, followed by payments of £45m ($61m) and £20m ($27m) in the following seasons, providing they are not promoted back to the Premier League.

On the face of it, you would say that payments like these would be enough to guarantee promotion back to the Premier League. After all, Cardiff has just been promoted without spending even 50% of that amount. But a club does not get relegated without poor performances on the pitch being matched by mismanagement off the pitch.

No club exemplifies this better than Sunderland, who have tumbled from the Premier League to League One in two seasons and who will find themselves contractually obliged to pay one of their players £44,000 ($59,600) a week next year, in a league where the average weekly wage is £1,500 ($2,030).

Getting back up

As I’ve written above, Sunderland, Hull, and Middlesbrough were relegated last year. Sunderland has been relegated again; Hull has finished the Championship season in 18th place, while Middlesbrough finished 5th, qualifying for the play-offs where the bookmakers rate them as a 3-to-1 chance to go back up.

If we look back just ten years to the 2007–8 season, Portsmouth, Wigan, Middlesbrough, Sunderland, Bolton, Fulham, Birmingham, Derby, and Reading were all in the Premier League. Now Portsmouth is in League One, where Sunderland will join them next year. Wigan has just been promoted to the Championship, where they will play Bolton, Birmingham, and Reading next year – all of whom were much closer to relegation than they were to promotion. Middlesbrough, Derby, and Fulham are in the play-offs: one of them may be back in the Premier League next year.

So relegation from the Premier League is both expensive and – potentially – for a long time. But the players who leave the relegated teams will find other clubs; the managers will manage somewhere else, and the gaping holes in the balance sheet may well be repaired by the next Chinese conglomerate to decide it needs to own a slice of English football. The people who pay the real price are the fans: spare a thought for the supporters of Stoke, West Brom, and Swansea who – at around 4:45 p.m. on Sunday – will be waving a tearful farewell to the Premier League and wondering how they came to swap an away day at Manchester United for one at Wigan Athletic…